Beyond the technology

Learning under fire: New Kobo report documents attacks on education in rural Colombia

“Rural schools in Colombia have been forgotten.” - Teacher in Chocó, Colombia

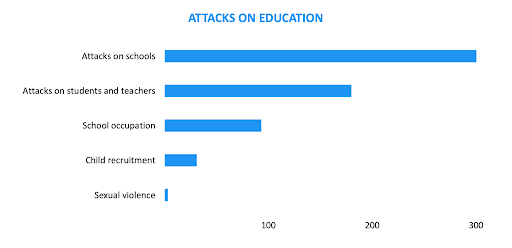

These words reflect the ongoing reality that teachers and students face in conflict-affected areas of Colombia, where an attack on education occurred approximately every three days in the first half of 2025. To advance efforts to protect education, Kobo’s Research Team conducted a large-scale survey across four of Colombia’s most affected departments to collect firsthand accounts of attacks and the strategies that teachers, communities, and local ministries use to prevent them. The report, “Learning under fire: Attacks on education in Colombia, 2020-2025,” documents over 600 attacks and the killing or injury of more than 140 students and teachers since 2020 in Antioquia, Chocó, Nariño, and Norte de Santander departments.

Despite the 2016 Peace Agreement, ongoing ceasefire negotiations, and the endorsement of the Safe Schools Declaration, conflict violence in rural Colombia continues to place students and teachers at risk. Shootouts and explosives near schools, threats against teachers, occupation of educational facilities by armed actors, and child recruitment along school routes remain widespread.

Based on interviews with 800 teachers, key findings from Kobo’s new report highlight the scale of violence and its effects:

- Head teachers reported over 2,800 days of school closures due to attacks.

- Around two-thirds of schools occupied by an armed actor were subsequently attacked by a rival group or force.

- Schools near military bases and police stations were at greater risk, with 40 schools—nearly 15% of those studied—attacked during clashes between armed groups and government forces.

- Attacks resulted in students dropping out, teachers resigning, psychological distress among students and educators, and a decline in educational quality.

- Approximately 10% of students at impacted schools dropped out after an attack, with girls more likely to drop out than boys.

- Teachers and communities implemented strategies to keep students and staff safer, including community dialogues to promote schools as peaceful spaces and establishing early-warning systems.

The impact of attacks and school occupations on students and teachers

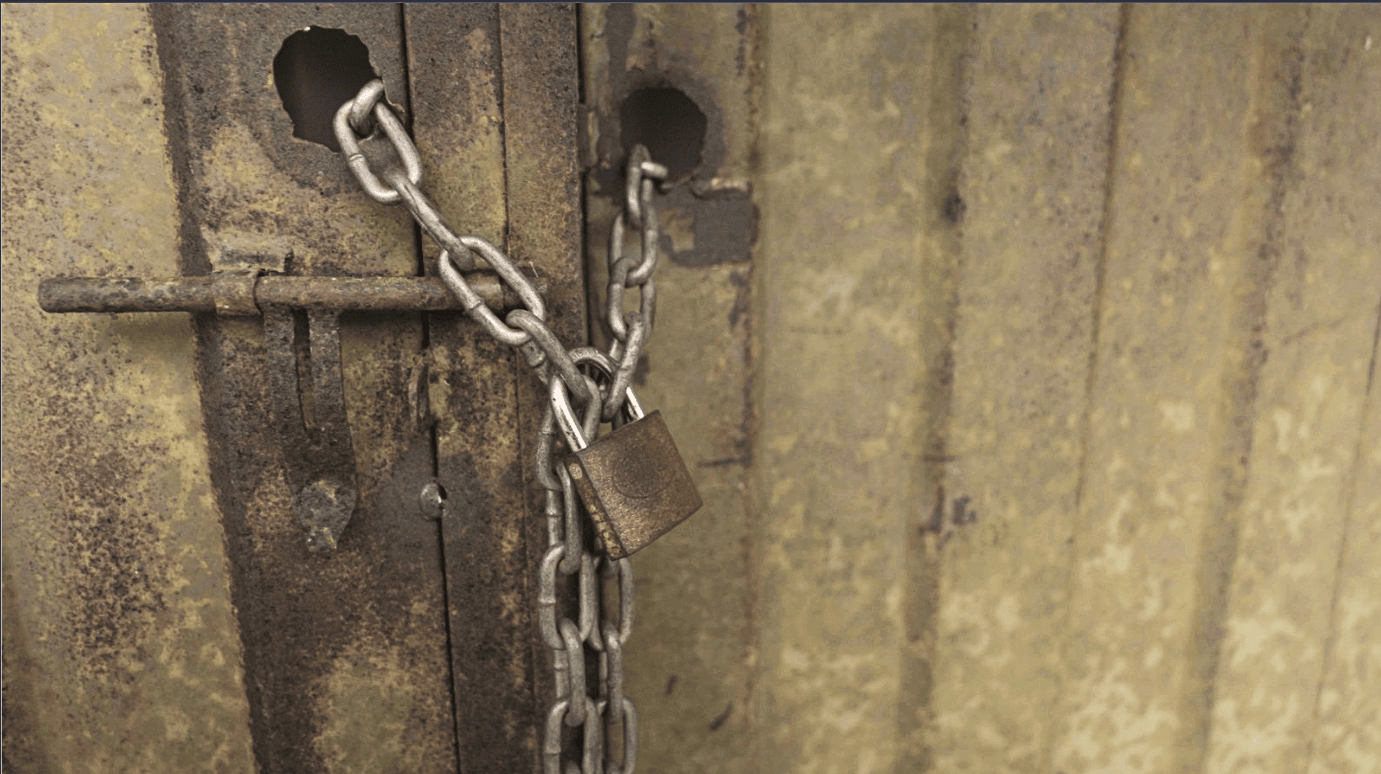

In conflict-affected areas of Colombia, dedicated teachers work to create safe environments and ensure students learn despite regular threats. Nonetheless, occupations of schools by armed actors—as bases, defensive positions, or weapons stores—are widespread.

Kobo’s “Learning under fire” report documents 93 cases of schools occupied by armed actors over the past five years. On average, school occupations lasted 65 days. When schools were forced to close during occupations, only slightly more than half of students were able to continue learning, often through virtual classes. Some of the schools sustained limited or moderate damage that required repairs, especially to windows, doors, and kitchen facilities.

Head teachers reported that armed actors often occupied schools in the morning or at midday while students were still in class. In some cases, schools remained open, so educators had to continue teaching in whatever space was left for learning in these small rural institutions. Other times, they resumed classes after the buildings had been occupied overnight.

“They entered through the window, took out the supplies from the school restaurant, used the bathrooms to clean themselves, and left everything very dirty with cigarette packs, tuna cans, and condoms, which subsequently the teachers had to clean up the next day before the children arrived and check if there were any risks.” - Male head teacher, Nariño department

The Research Team found that armed actors occupied schools for their strategic location and facilities, like kitchens, running water, and electricity. Although occupations were reported in both the rural countryside and towns, schools in rural areas were occupied by armed actors for longer periods as bases, while schools in towns were generally used for shorter periods for meetings, internet access, and brief rest stops.

School occupations and attacks take a significant and long-term toll on the psychological wellbeing of the education community. Around 25% of teachers in the study reported signs of post-traumatic stress disorder after an attack, with women slightly more affected than men. They described experiencing disturbing or unwanted memories or dreams, loss of interest in activities they once enjoyed, difficulty concentrating, and being extra alert.

“Many teachers were in constant fear, and three female teachers were admitted to the hospital due to a nervous breakdown.” - Male school coordinator, Norte de Santander department

Teachers are calling for concrete action to make schools safer

“The best way to heal from violence is by giving students quality education that supports their wellbeing, fulfills their needs, and helps them keep dreaming.” - Teacher, Nariño department

The “Learning under fire” report amplifies teachers’ voices by highlighting their recommendations for peacebuilding, including:

- Mental health support for students and teachers that provides consistent, long-term care.

- Safer schools, including improved infrastructure, secure routes, and early-warning systems, complemented by safety training and protocols.

- Safe and speedy relocation of teachers when they are threatened by armed actors.

- Financial restitution for survivors of attacks and students and teachers impacted by conflict.

- Justice for survivors, from holding perpetrators accountable to stronger human rights protections.

A key recommendation from the report is that teachers working in conflict-affected contexts should be at the center of shaping and implementing new protocols to safeguard education. Their firsthand experience ensures the development of localized, practical solutions that make schools safer for children, teachers, and communities.

Advancing the protection of education through rigorous data and local engagement

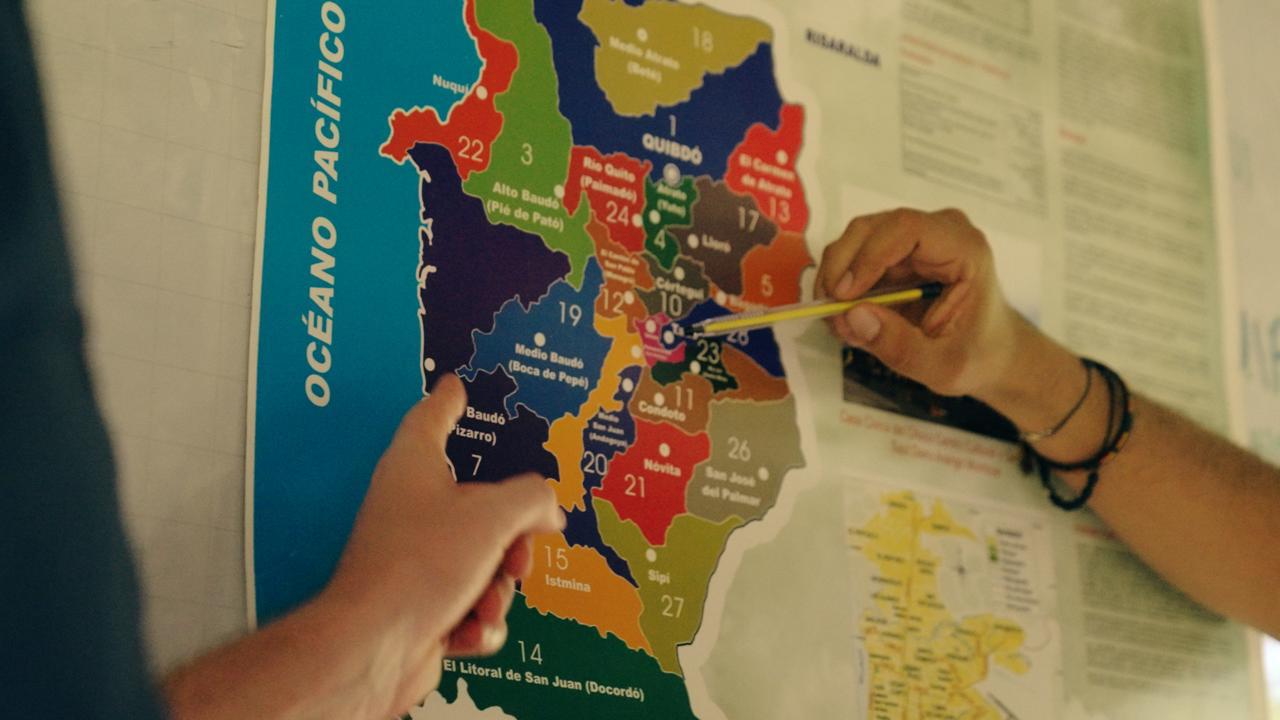

Reaching some of the most remote and under-served areas of Colombia despite accessibility challenges, Kobo’s research combined rigorous data collection with deep local engagement. Kobo provided a week-long training in survey best practices and ethics for ten local interviewers, who then conducted interviews with over 800 teachers in four departments. Data was thematically and statistically analyzed to produce report findings and recommendations.

As part of Kobo’s commitment to research with a social impact, the Research Team organized an official report launch in Bogotá to share findings with policymakers and affected communities. Attendees heard from representatives of local ministries of education in Norte de Santander and Quibdó about their firsthand experiences of attacks and the impacts on educational outcomes. Participants including education specialists, journalists, and legal experts discussed strategies for limiting and responding to attacks and supporting locally-led protection efforts. The event was also an opportunity to gather and share practical resources for safer schools with teachers. Speakers included representatives from the Ministry of Education, Jurisdicción Especial para la Paz (Colombia’s transitional justice mechanism), UNESCO, and local NGOs COALICO and Corporación Opción Legal, and the event was co-organized by Kobo with Save the Children-Colombia, LA CID, GCPEA, and Education Above All Foundation.

To encourage policy change and the adoption of report findings, Kobo’s Head of Research also held closed-door meetings with government and UN agencies as well as local humanitarian organizations to share actionable recommendations to better protect students, teachers, and schools. Kobo’s research in Colombia is a critical step towards disrupting attacks on education and ensuring that policies are evidence-based and locally-grounded.

Read Kobo’s full “Learning under fire” report at kobo.ngo in English and Spanish.